As I mentioned in my recent post I am planning to create a programming language to work with game engine I’ll be building in future hopefully. So that said where do we start “a new programming language” thing? Well as every other programming projects it would be great if we firstly design our language first. Letting project boundaries, goals, non-goals, steps and doing some considerations will help us in a long run to spend our time more reasonable, reduce needs of decision-making while implementation and also figure out how exactly will it function. It’ll also let us to re-evaluate whether or not does it really worth investing time to reinvent wheel?

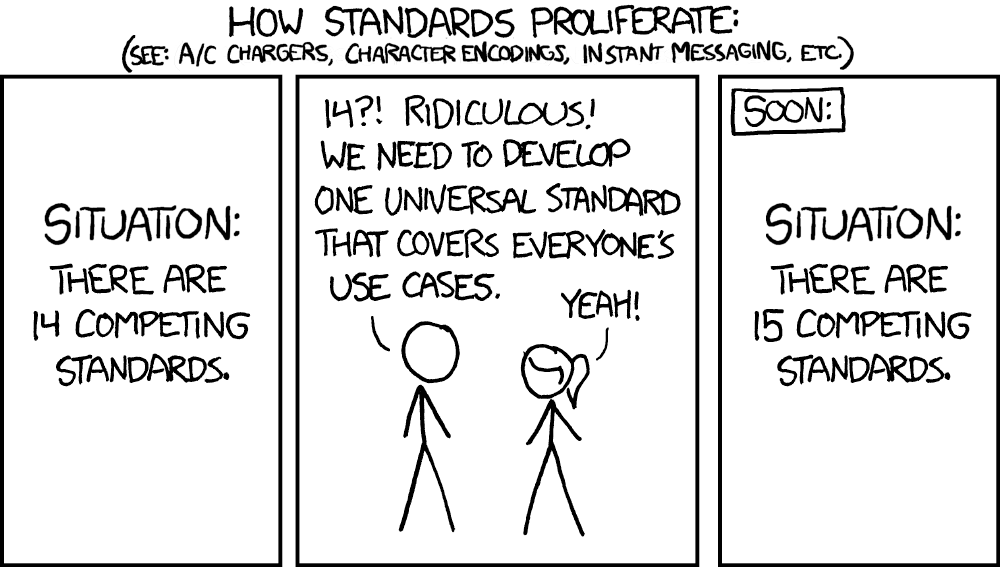

Of course we’re not going re-invent “the wheel”, but rather create a new universal wheel model that covers most of our use cases.

Well here I am with not invented here syndrome again trying to create something in thought of improving them but instead will probably going end up even worse. But anyways, unlike good-old days I am now aware of my tendency on NIH but I also learned that I’m going to earn more experience than wasting my time during that journey because I’m not someone writing programming languages daily - so I’ll be going to learn lots of new stuff. Long story short let’s dig into designing the language itself.

Static or dynamic typing

If you’ve read my previous article you’ve probably noticed that for some reason I’m not fan of dynamically typed languages. Mainly because I do not like to remember language APIs, third-party library APIs or heck I don’t even want to remember APIs for the stuff I written a week ago. I personally think our brains should instead focus on more important stuff than remembering things like x function accepts 3 arguments which first 2 of them should be number and 3rd could be either null or instance of class Y. That’s not even enough you’ll also have to remember which type of arguments does class Y accepts as a constructor. Of course I know that everyone writes self documenting code that doesn’t requires remembering types for untyped variables. But for everyone else there’s statically typed languages which instead of supposing reader already know what type does a variable named “data” accepts but instead explicitly provides that variable called “data” only accepts values in type of boolean (aka. bool).

And in addition to that the compiler will happily punish you if you try to put instance of Data class there instead of explicitly defined boolean value. Well who would call a variable for storing bool “data”? Well I won’t but there’s probably someone out there still using generic names like “i”, “it”, “item”, “element”, “data”, “entry”, “entity”. Uh, I know, it’s me (and probably you too). In all seriousness static typing adds so much value to the language that even most dynamically typed languages like javascript, php or python have either evolved first-party type support (php 7 type declarations, python 3.10 type hints), or widely adopted a third-party extension for types (typescript) or planning to do so in future. Heck I remember when I wasn’t aware of typescript, I used JSDoc comments to hint my types in javascript so that when I reference that variable from somewhere else my IDE could suggest properties to me because as project grows there’ll be lots and lots of things you need to remember and I kept forgetting things like options keys as growth happened.

There’s also additional bonus of writing static typed code that in some cases compilers can also link things together in compile time so the runtime would not have to deal with figuring out where is the variable stored. What does “linking” means / has to. Let me explain for a moment.

var user = {

name: 'John',

age: 23,

};

console.log(user.age);

Take the above js code for example. To print “age” of “user” the runtime has to do hash map lookup in order to find out where does value of age stored on memory. Hash maps are fast for that use cases of course, you can lookup in O(1) time complexity in optimal cases. But still to find address of value the runtime will have to calculate hash of “age” (or might use pre-calculated value instead) and then mod that has variable with the capacity of hash map and then in a good condition it’ll find out that the value is stored at memory address of:

(starting pointer of `user`) + ((hash of "age") % (capacity of `user`)) * (size of one map entry)

Remember that all those operations only done to evaluate user.age once. During program lifetime you’ll usually need to access properties lots and lots of times. And addition to that js stores global variables in some sort of global object / hash map (window in browser, global in node, globalThis in both environments). So to resolve “user” value in above example the runtime will firstly have to do hashmap lookup to find out pointer to user object itself then will do another lookup to find “age” value.

But in a statically typed language it’s possible for compiler to pre-calculate pointer addresses (at least offset from some starting address) so that runtime doesn’t have to do hash map lookup for resolving named values (properties, variables, functions, methods, etc..). Why tho? Because compiler can figure out that when you access “age” property of “user” which is instance of “User” class and it’s value starts from nth byte of instance which n could be calculated using:

(class header) + (size of "name" property header) + (size of "name" property value)

Please note that this calculation will be done during compilation and the result will be hardcoded into bytecode or machine code to be used during runtime.

In conclusion, one of my goals with this language is that it has to be statically typed language. It’ll also support object oriented programming (classes, methods, properties). Because even if I won’t add OOP support into it, people can try to mimic oop features by writing some hacks. For example for a long time javascript didn’t supported classes. But eventually people started using other features of language to mimic OOP in javascript like:

function User(name, age) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age

};

User.prototype.printAge = function() {

console.log(this.age);

}

var user = new User('John', 23);

user.printAge();

So instead of giving overhead of “re-implementing oop in X language” to users, I want it to support classes from the beginning. Of course that also includes class features like methods, properties, constructors and maybe access modifiers.

To be or not to be

One of the features of most widely used programming languages is null literal value, which could be used for reference values without a reference. While null seem to be a great idea, over the course of time it caused lots of systems to crash with NullPointerException-s and added another layer to some type systems for declaring whether or not the variable could be null. In fact even inventor of null said that it was his billion dollar mistake which he made because it was too easy to implement in 1965 and yet we’re still stuck with it. But I’m not sure about whether or not should I add null to the language. Because if I were to get rid of null literal, people will need an alternative to it, because it’s a feature that we built convention over the years of using it so removing that will force people to either complain about it or re-implement that themselves just like how functions used as classes in javascript before class was introduced to the language.

One of the ways of providing features of null while not actually providing null values is adding some sort of null safety type checks. This adds another layer to type system and mental model in order to work because now you can’t just think about types themselves but you’ll also have to take nullability flag into consideration. And also you’ll going to add new features to the language to reduce boilerplate like operators: identifier?.property, nullableValue! .

Another way came in my mind is how rust handles value nullability. Rust has a type called Option<T> which provides interface for providing and consuming values that either has Some value or None value. Here’s how it looks like:

let value = Some(5);

match value {

Some(x) => println!("value = {}", value),

None => println!("value is not available"),

}

Rust uses a language feature called algebraic data types (ADT) for implementing Option<T> interface. It’s a way of creating types that could be union of multiple interfaces. What I like about that type form of null alternative is it doesn’t add a new layer of complexity but instead uses already existing language feature.

Here’s how rust implemented nullable type alternative:

pub enum Option<T> {

None,

Some(T),

}

But for us this also means we have to support ADT to use this null alternative. Not only ADT but as you can see it uses generic types too for implementing this feature. Of course we’ll need generics in a static typed language to reduce code repetition. But I wasn’t planning to implement it at the beginning.

Of course the third option would be adding null literals without strong null checks (null safety). This is how lots of languages today handle null values. But as time passed languages which didn’t support null safety, slowly but surely adopted it like C# and Dart. And languages which become popular recently came out with null safety from day one (Kotlin or Swift for example). So it’s not hard to see that null safety is kind of industry standart nowadays. But as of now, I’m still not sure which path should I follow and instead I’ll try to decide this later on based on other decisions. For example If I were to implement ADT and generics I’ll probably go with rust way, otherwise I might consider adding nullable type annotations instead. Or in a small chance I might find out another way of implementing alternative to null.

References:

Syntax

I personally like C-like syntax instead of things like s-expression (lisp) or indentation (python) derived syntax. And since I am the one who’s going to create it, I’ll be going to stick to my preference and use C like syntax design on new language. But aside from general style we still have to design syntax for individual statements. So let’s dig into it and try to specify design for primary statements used in programming languages. In general here’s things we have to design syntax for:

- Variable declaration

- Function declaration

- Class declaration

- Method

- Property

- Statements

- Condition statement

- Loop statement

Variable declaration

For now I’d like to use var keyword to declare a new variable in current scope. Something like:

var name = "John"; // implicit type declaration

var age: int = 23; // explicit type declaration

As you can see it’ll be possible to declare variables both implicitly or explicitly typed. When implicitly typed, compiler will try to figure out type for the variable from the given context. But if compiler couldn’t figure out for some reason, it might throw a compile time error and force user to explicitly type the variable.

Also I want to add shorter version for implicit type variable declarations using := operator like Golang.

name := "John";

This might seem unnecessary feature, but we’ll going to see that it’s more cleaner looking when we’re going to use declarations in statements like if conditions.

By the way you might ask why not just use name = value equations for both declaring new variables and also assignments. Well, the reason is simple. Compiler have to distinguish between declaration and assignment to decide when to create a new variable and when to use existing one. This also going to help you notice typos on code like:

updated := false;

if (!updated) {

preformUpdate();

uptaded = true;

}

This code won’t going to compile because the variable called uptaded is not declared in the scope, because there’s a typo in variable name. If our code used usual assignment operator for declaring new variables we might have hard time trying to figure out why our code will not work even if we put breakpoint on line uptaded = true; and validate that it actually gets executed.

Function declaration

Nothing much to say there because more or the less almost all the languages uses similar syntax for function declaration, so we’re not going to be different too. Here’s how functions could be implemented in our new language:

func function_name(arg1: int, arg2: int): int[] {

// ...body

return result;

}

For functions that doesn’t indeed need to return any value, you can indeed ignore return type.

The language will be also going to support anonymous functions which is also called lambdas in some languages. Lambdas in general usually useful when using functions as values.

isEven := func (n: int): bool {

return n % 2 == 0;

}

Classes

As I mentioned above I want this language to support object oriented programming from day 1, because that’s one of the features we used to see and use regularly. In first I thought about using a bit different model, something like mix of rust structs, traits and implementations with OOP paradigm of typescript, C#, java. But then I decided to just stick to simpler design and use OOP paradigms we’re already using for years. So as other OOP supported languages classes in our new language will support inheritance, interface implementation and other known features as well. Syntax itself looks almost similar to typescript class declaration syntax.

class User extends Model implements IDisposable {

name: string;

age: int;

User(param1: string, param2: int) {

this.name = param1;

this.age = param2;

}

dispose() {

// free resources

}

}

Condition statements

To make our language Turing complete we have to introduce conditional statements into our language. The syntax for if statement will be mix of C and go style if statements like:

if (statement1; statement2; ...; booleanExpression) {

// then branch

} else {

// else branch

}

So with that ability you can write code like:

if (var result = doSomething(); result.hasError) {

print("Unfortunately doSomething returned result that contains an error");

}

Or because we’ve introduced shorter way of variable declaration you can write like this too:

if (result := doSomething(); result.hasError) {

print("Unfortunately doSomething returned result that contains an error");

}

Loop statements

I’m going to use go style loops here too. Why? Why not, you can use same for keyword for declaring multiple forms of loop at once while other languages uses multiple keywords for different syntax.

Regular C style for loop:

for (i := 0; i < 10; i++) {

print("i = ", i);

}

Infinite loop:

for {

print("...");

}

Conditional loop:

for (!paused) {

render();

}

Iterator loop:

for (var user in users) {

print("user logged in: ", user.name);

}

Our language design syntax is could be considered somewhat completed. Let’s move on to next steps to make some more decisions.

Goals

Well we have somewhat completed syntax design for our language, but why do we need another language? What’s our goals with this project? Asking this kind of questions is important during the design phase of projects because it lets us to avoid feature creep and focus on what’s important for us. In the end we’re human and we’ll eventually get bored, so we have small time frame until we get into that stage and we have to use that time more effective. So let’s define our goals with this project.

C style syntax

Having familiar style of syntax will reduce learning curve for newcomers to the language. And also will reduce decision making during the project development.

Static type system

I’ve already listed my reasoning on this goal on static or dynamic typing section above.

Embeddable

We want to use that language for scripting on our game engine, so the language should be easily embeddable into different projects. To make a language embeddable the language should have an interface which could be used to add foreign functions into it, register types, share data with embedded system and so on. Foreign functions are a language feature that let’s you declare functions inside language and implement it in another language or system. For example you can add a function named “print” into your language and write implementation in runtime side like:

void init_vm(VM *vm) {

vm->define('print', &vm_print);

}

Value vm_print(Value []args) {

for (auto arg : args) {

std::cout << Value::toString(arg);

}

return Value::boolean(true);

}

The code bellow is written for demonstration purposes, foreign function interface API might be written differently during the implementation.

Performance

While performance is not one of our main goals for initial versions, as time passes we have to put some effort into making our language performant as much as possible, because in the end our main goal is to use this language on our game engine that hopefully we’ll be building in future.

For initial implementation I am planning to start with simple recursive Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) visitor type interpreter which does not preform good as alternatives but good enough for our starting point. But afterwards we can implement bytecode interpreter to increase runtime performance and use some advantages like CPU caches. If you don’t have any clue on what’s the difference or even what does AST visitor and bytecode interpreter does, let me quickly explain.

AST visitor

Abstract syntax tree is representation of human written code in tree structured way which makes it easy to process by programs. For example take the following example code:

var a = 5;

if (a > 3) {

a = a + 2;

}

The following code could be represented as AST like this:

{

"type": "Program",

"body": [

{

"type": "VariableDeclaration",

"name": "a",

"init": {

"type": "ConstantExpression",

"value": 5

}

},

{

"type": "IfStatement",

"condition": {

"type": "GreaterThanExpression",

"left": {

"type": "IdentifierExpression",

"name": "a"

},

"right": {

"type": "ConstantExpression",

"value": 3

},

"thenBranch": {

"type": "ScopeStatement",

"body": [

{

"type": "AssignmentExpression",

"left": {

"type": "IdentifierExpression",

"name": "a"

},

"right": {

"type": "AdditionExpression",

"left": {

"type": "IdentifierExpression",

"name": "a"

},

"right": {

"type": "ConstantExpression",

"value": 2

}

}

}

]

}

}

}

]

}

Yes it’s a lot bigger than the original code, but it’s a lot easier to understand for programs, and also you can run the following data structure without any further processing needed. You can simply create a for loop that iterates items in the body of first Program node, and executes each node according to its type and given properties. That’s what AST visitor interpreter does behind the scene. It parses raw code into easy to understand form of AST and then walks over nodes one by one. It’s easy to understand and implement this kind of interpreters so that’s why we’re going to implement AST visitor interpreter for starting point.

But, if you know a bit about data structures and especially trees, you might now that tree nodes connected to each other with heap pointers, and those pointers might be scattered across the memory. When you walk through the tree program would have to resolve values from different chunks of memory. Memory itself is pretty fast but you know what’s faster? CPU cache. Modern CPU’s has their own small but very fast built-in storage that used to cache frequently accessed memory chunks. The key points here is that CPU cache has limited space and it caches frequently accessed memory chunks. But in our case AST nodes could be spread over different chunks of memory - which results CPU not caching the part we need very fast access. To simplify, CPU cache will work well for string of data that’s stored near each other on memory rather than spread out data.

Soo, to gain even more performance boost from CPU cache we can optimize our implementation which will be our next goal - bytecode interpreter. Bytecode interpreters works similar to hardcoded interpreters inside CPU that acts on machine code. But instead of machine code, bytecode interpreters uses its own set of instructions which is not dependent on device it’s running on. Bytecode itself is just string of bytes that simply stores our program. But instead of tree like structure, our program flattened into array structure so that the whole program could be loaded into nearby chunks of memory.

To convert above example code into bytecode we first have to define opcodes for our bytecode. Opcode is simply fixed size (usually 1 byte) codes representing different operations.

OP_CONST // constant

OP_DECL // declare variable

OP_GET // get variable value

OP_IF // if statement

OP_GREATER // greater than expression

OP_ASSIGN // assign value to variable

OP_ADD // add 2 values

OP_NOOP // no operation

Using the above opcode map we could transpile the code pseudo bytecode like that:

constants = [

5,

"a",

3,

2,

];

instructions = [

OP_CONST, // push constant value to stack

0x00, // address of constant value: 5

OP_DECL, // declare a new variable and initialize with popped value from the stack

0x01, // address of the variable name: "a"

OP_CONST, // push constant value to stack

0x02, // address of constant value: 3

OP_GET, // push variable into the stack

0x01, // address of the variable name: "a"

OP_GREATER,// pop 2 values from the stack and compare them with > operator and push value into the stack

OP_IF, // pop value from the stack, if the value is false then jump to given address

0x12, // instruction address of else branch

OP_CONST, // push constant value to stack

0x03, // address of constant value: 2

OP_GET, // push variable into the stack

0x01, // address of the variable name: "a"

OP_ADD, // pop 2 values from the stack and add them to each other then put result to the stack

OP_ASSIGN, // pop value from the stack and assign it to the variable

0x01, // address of the variable name: "a"

OP_NOOP, // no operation because else branch starts here (0x12), but there's nothing left to do

];

As you can see it’s a lot easier to execute this code since instructions are so much simplified and the whole code could be stored in single memory chunk. But generating bytecode from complex code is a bit trickier than said so I’ll be probably going to implement bytecode interpreter on later stages of development instead.

Note: Provided AST and opcode representations are not used by any specific compiler it’s just a simplification for demo purposes.

Chicken or egg?

You might ask yourself that if compilers written using another compilers, how did first compilers were invented in the first place? Well the answer is actually quite simple. Someone had to hard code a compiler program into punch cards. It didn’t ever needed to be perfect because they could use that compiler to compile even better compiler for future uses. In same manner moden languages can also have compilers written in the same language, but before that they need to create a simple compiler in another language to compile first compiler in source language. If you want to dig deeper into this concept in Computer Science it’s called bootstrapping.

But as for ourselves, we don’t need our compiler to be written in source language. We are going to use it for embedding into another programs, so it’s better to write compiler in well known language to make embedding easier. But which language are we going to write our compiler with?

Short answer is C++ most probably. Because building compilers with low level memory access with pointer artimetrics is makes it easier to implement different parts especially when implementing bytecode virtual machine. For example uint8_t *ip; holds both pointer to current instruction, you can advance it by adding +1 to it and you can dereference it without needing another variable. Otherwise you’ll have to store 2 variables first one for storing bytecode array and second one to store instruction index in that array, and to dereference instruction you’ll have to use code[ip] which is not a huge deal breaker but I prefer first option.

Conclusion

This article is already very long and I don’t have anything else to say to be honest. To conclude the article I am planning to create a programming language that we’re designed together above to use in game engine Ill be building in future. The language will be C-style, statically typed and the compiler will be embeddable to other systems alongside with ability to be extended using foreign functions support.

Thanks for reading till this far 😇